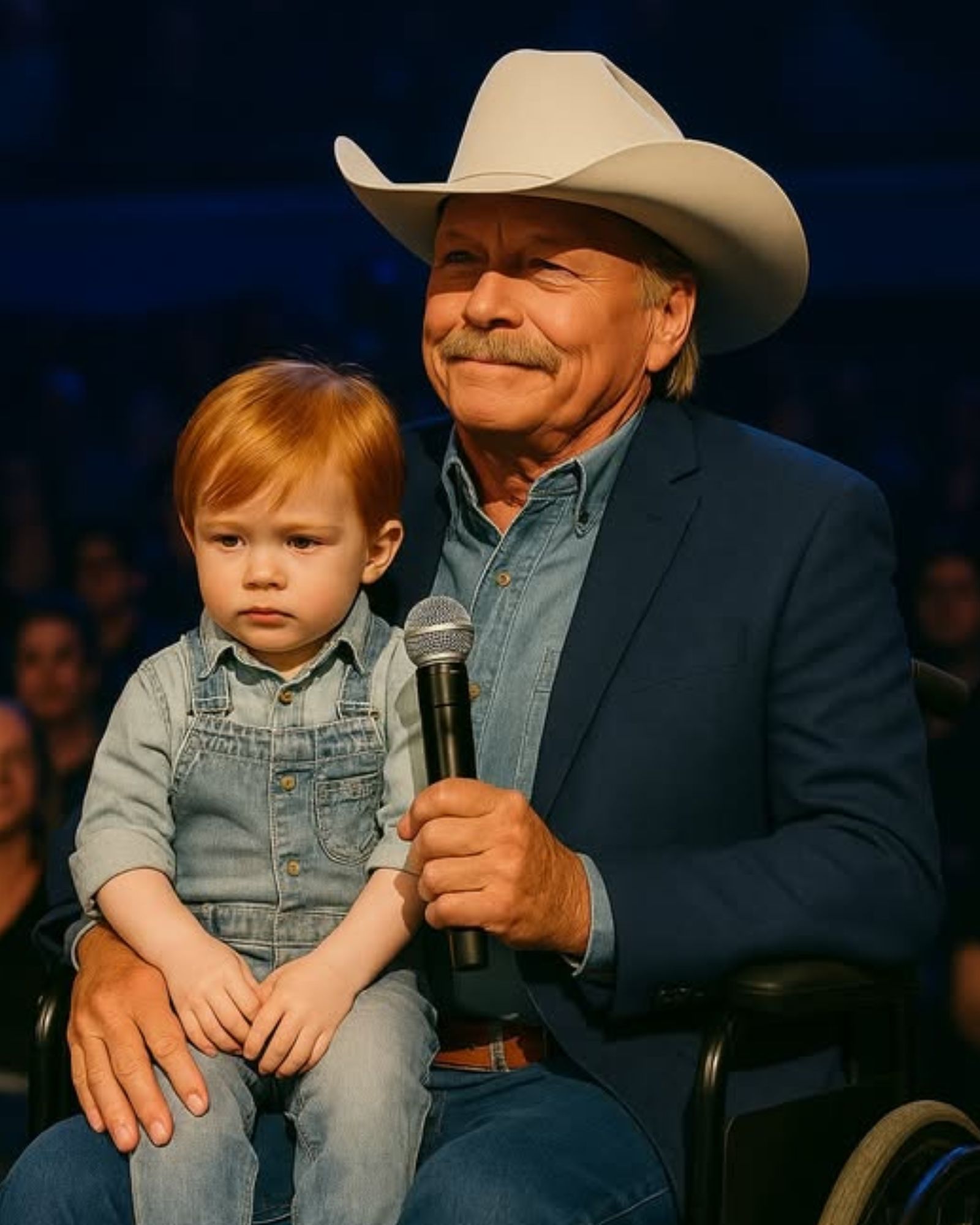

“This is the next diamond,” Alan Jackson whispered with pride in his eyes, and in that moment, his concert became something more than music—it became a beautiful glimpse into the future. The music paused as the country legend bent down to kiss his young grandson, a little boy who looked just like him, and the entire arena held its breath, witnessing not a superstar, but a grandfather sharing his legacy. It wasn’t a rehearsed part of the show; it was a raw, beautiful moment of family love playing out on the world’s stage, leaving every heart in the crowd melted and fans completely amazed by the quiet promise of what’s to come for country music.

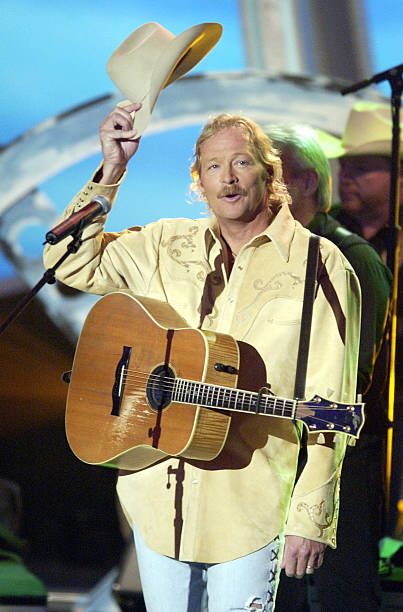

I remember the lights dropping first—an arena-sized inhale at Bud Walton, the kind that makes even a veteran critic sit up a little straighter. Then the band slid into that unmistakable mid-tempo groove, a shuffle that’s equal parts wry smile and steel-soled stride. Alan Jackson, hat brim low, ambled to the mic as “Gone Country” unfurled its opening bars, a statement of intent for a night pitched as Last Call but delivered with the clarity of a first toast. The choice to open with this song is savvy: it’s both a calling card and a thesis, a road sign for the long highway of his career that says, simply, follow me. Fayetteville answered.

To situate the moment, it helps to remember where “Gone Country” comes from. The track first appeared on Alan Jackson’s 1994 release Who I Am for Arista, produced by Keith Stegall—a partnership that shaped Jackson’s signature mix of plainspoken stories and bright, radio-ready polish. Songwriter Bob McDill penned the lyric, a sly panorama of singers chasing new horizons in Nashville; Jackson took it to No. 1 on Billboard’s Hot Country Songs on January 28, 1995. That’s the history the Fayetteville crowd carried into the room, whether they knew the dates or just felt the era in their bones.

Live, the arrangement honors the record while leaving room for breath. The rhythm section lands with easy confidence—kick drum round and present, snare trimmed to a dry pop that keeps bodies moving without bullying the tempo. A bright, right-of-center electric lead carves filigree around the vocal, the sort of unfussy guitar work Nashville players make sound inevitable. When the steel enters, it’s not a tearjerker’s moan so much as a glinting commentary—ironic eyebrow, not lament. Fiddle lines brush the top end like a warm breeze through a screen door.

Jackson’s baritone remains the anchor. On this night it had that familiar light rasp at phrase ends—less strain than silvering, the burnish of time lending weight to words that have always walked the line between satire and salute. He doesn’t oversell consonants; he rounds them, letting tone carry meaning. You hear it when he sketches those vignettes—Vegas lounge, Greenwich Village folkie, San Fernando Valley commuter—and you sense how kindly the performance holds them, even as it ribs. That balance has always been the song’s trick.

There’s also the matter of space. In a big building, air is its own instrument. Bud Walton’s tail on the cymbals added a soft afterglow to the two-and-four, and the vocal reverb was dialed just long enough to suggest distance without smearing diction. The band’s stagecraft keeps lanes clear: low strings and bass sit center-left, steel blooms on the right like an open field, and the electric’s fills drop in the cracks. You could diagram the traffic and it would look like a tidy small-town grid.

I listened for the acoustic bed and found it doing essential, invisible work—chop and shimmer, the heartbeat on which everything rides. When keys peeked through, they were earthy, closer to barroom piano than cathedral pad, a reminder that “Gone Country” isn’t a sermon; it’s a tour of the neighborhood. One tasteful organ swell, then back to the pocket. That kind of restraint is an old Nashville virtue and a current superpower for Jackson’s road band.

Because the set used “Gone Country” as an opener, its lyrical point landed with extra relish. Any late-career victory lap risks slipping into mere nostalgia. This song refuses that frame. Under the hat brim, Jackson sounded less like a legend memorializing glory days and more like a working artist enjoying his best tool: a story that still fits the times. The room heard it and responded with the kind of roar that arrives not at the chorus but at the first ah, yes—recognition sparking before memory.

“Gone Country” is, famously, a mirror. Some hear it as a jab at carpetbaggers; others hear welcome-to-the-party. Jackson himself has long framed it as celebratory, acknowledging how country’s tent widened in the ’90s. Watching him sing it now, you catch a shade of both. His phrasing carries that gently teasing edge on “learned a few new words” while the band lifts the chorus like a porch-light turning on. The performance leaves room for the audience to decide, which might be the only way a song this widely loved keeps breathing.

I kept thinking about the path from studio to arena. On Who I Am, the production framed Jackson as a neighbor who could headline any state fair and still sound like a man you might meet in the grocery line. Live in Fayetteville, that tone survived scale. Maybe it’s the mix: guitars crisp but not brittle; low end warm rather than sub-booming, which would have flattened the swing. Maybe it’s the players’ discipline—no one rushing fills, no one hammering eighth-notes in the name of energy. Or maybe it’s Jackson’s vocal economy. He doesn’t chase applause with elongated melismas. He gives you the line, then he gives you the next one, as if trusting the song to do its job.

As a piece of music, “Gone Country” endures because it is cleverly built. Verse one maps a character in just a handful of strokes; verse two and three widen the canvas; the chorus functions as both hook and hypothesis. Harmonically, the tune keeps to familiar roads, but the momentum depends on pocket and color. You can tell the band knows where the ear lives—right there between snare and acoustic strum, in the conversation between steel ornament and lead fill. When the bridge arrives, it’s a wink more than a modulation; the payoff is rhythmic rather than harmonic, and that’s precisely why it plays so big in a live room.

As for the social edge, the song’s target shifts with each era. In the mid-’90s, it scanned as commentary on newcomers to Nashville’s commercial boom. Tonight, it reads more like a parable about how every genre that expands becomes the city it attracts. In a world of quick pivots and strategic branding, “Gone Country” cautions that the map is not the territory. What matters—Jackson seems to say as he grins through the last chorus—is whether you can carry the tune, tell the truth, and leave folks humming on the way to the parking lot.

A pull-quote from my notebook keeps circling back:

“Country is a place in this performance, not a costume—built from time, tone, and the grace of musicians who know when to leave a space unfilled.”

The Fayetteville crowd knew it, too. A couple sat two rows ahead of me—she in a denim jacket with a ’90s tour patch, he in a Razorbacks cap. During the second chorus, they turned to each other, both laughing at a private memory you could almost see: a first apartment, an old truck that never idled right, a radio that only pulled three stations and made this sound like a transmission from a friend. Micro-stories like that were happening all around the bowl. You sensed it in the way people sang the tag without straining, as if speaking a familiar family phrase.

Another vignette: a high-school kid a few seats down, filming on his phone until the battery choked, then tucking the device away and, for once, simply listening. When the steel player let a note feather out to the rafters, the kid leaned forward like someone hearing a language he didn’t know he knew. In a marketplace hooked on the new-new, it’s striking to watch a song from 1994 make a room full of ages feel contemporary. That’s not nostalgia; that’s craftsmanship.

And one more: outside after the encore, a man in his sixties held the arena door open for a cluster of strangers while he whistled the refrain, the kind of unconscious generosity live music sometimes unlocks. “That opener,” he said to no one in particular, not bragging, not analyzing. “That opener was it.” He meant “Gone Country,” of course. Start the night with a song that explains the night.

If you want to go inside the mechanics, you can. You can talk about the way the drummer’s right hand leans back a hair on the ride, giving the groove a waltz-adjacent sway without ever leaving four. You can talk about the lead guitarist’s choice to avoid modern drive textures and stick with something clean and articulate, allowing the steel to own the sustain narrative. You can admire the subtle keys work—closer to honky-tonk piano coloration than glossy pad, which keeps the mix terrestrial. But the real secret is how all those choices protect the lyric. Every instrument behaves like a camera angle, keeping the vocal in focus and the story legible.

There’s an audio angle, too. In an era of bombastic bottom, the concert’s sound favored definition over sheer pressure. If you listened with the sort of curiosity that later sends people shopping for studio headphones, you heard phase-coherent backing vocals tucked just under the lead, a bass presence that warmed the room without masking the kick, and a treble band that traded sparkle for texture. Nothing fatigued. Everything invited you to stay.

Context matters, and Jackson’s team knows it. The Last Call tour has been presented as a final lap—the artist honoring milestones while acknowledging the realities of time and health. To choose “Gone Country” as the gateway says: I’m still interested in the conversation. The song isn’t just a hit; it’s a lens, a way to think about the genre, the industry, and the porousness of borders. On this night in Arkansas, it felt less like a greatest-hits obligation and more like a handshake before the stories begin.

Any review of “Gone Country” benefits from a glance back to its chart life and its recording DNA. The Who I Am lineage—Arista, Stegall, McDill—remains the song’s fingerprint, and its rise to the top of Billboard’s country ranking is a matter of record. But faithful context is only half the duty. The other half is listening to how the song lives now. In Fayetteville, it lived like this: strangers harmonizing in a key that suits memory; a veteran singer whose voice carries a new kindness; a band that plays like a well-worn porch—sturdy, sun-warmed, inviting.

If you’re the type who upgrades your premium audio setup at home, you already know that replaying a concert performance often reveals details you missed in the room. What stays with me here, though, isn’t a solo or a single sonic flourish. It’s the discipline. Jackson doesn’t chase novelty. He trusts song shape, band empathy, and the quiet drama of a melody landing squarely where it belongs. He trusts the audience to hear the wink and the welcome coexisting. He trusts “Gone Country.”

And that trust is contagious. By the final chorus, the thought arrived uninvited and grateful: these are the nights when country music leaves the museum and remembers it’s a front porch.

Step back and the larger arc comes into view. From a 1994 studio cut to a 2024 tour opener, “Gone Country” has earned its place as an American standard—the kind of number younger artists cover to signal literacy and older artists play to remind us how songs can hold time. It’s part of a body of work that made Alan Jackson both a radio fixture and a storyteller’s north star. You don’t need a manifesto to explain why it still works. You just need a room, a band that listens, and a singer who knows that plain speech can sing.

Walk to your car and try not to hum it. The road out of Bud Walton is a chorus in itself—brake lights in sequence, windows cracked to let the night in. Somewhere in the traffic, someone will flip to a station that still plays ’90s country on purpose. Somewhere else, a kid who “doesn’t listen to country” will load the studio version, surprised by how easy it sits. “Gone Country” has a way of doing that—traveling light, saying something, leaving you with more air than you had when you came in.

Listen again tomorrow. The song won’t go anywhere. It never needed to.