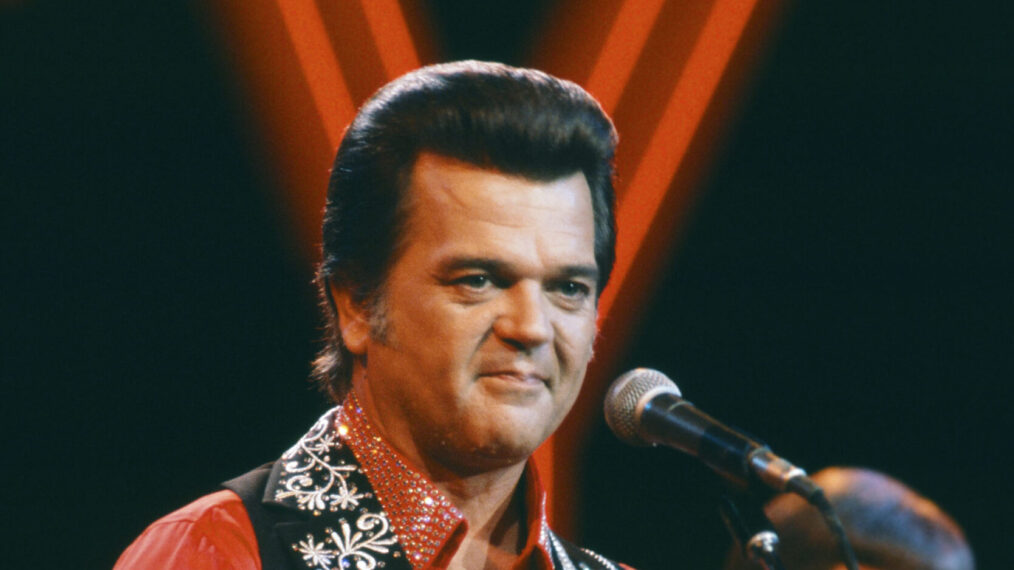

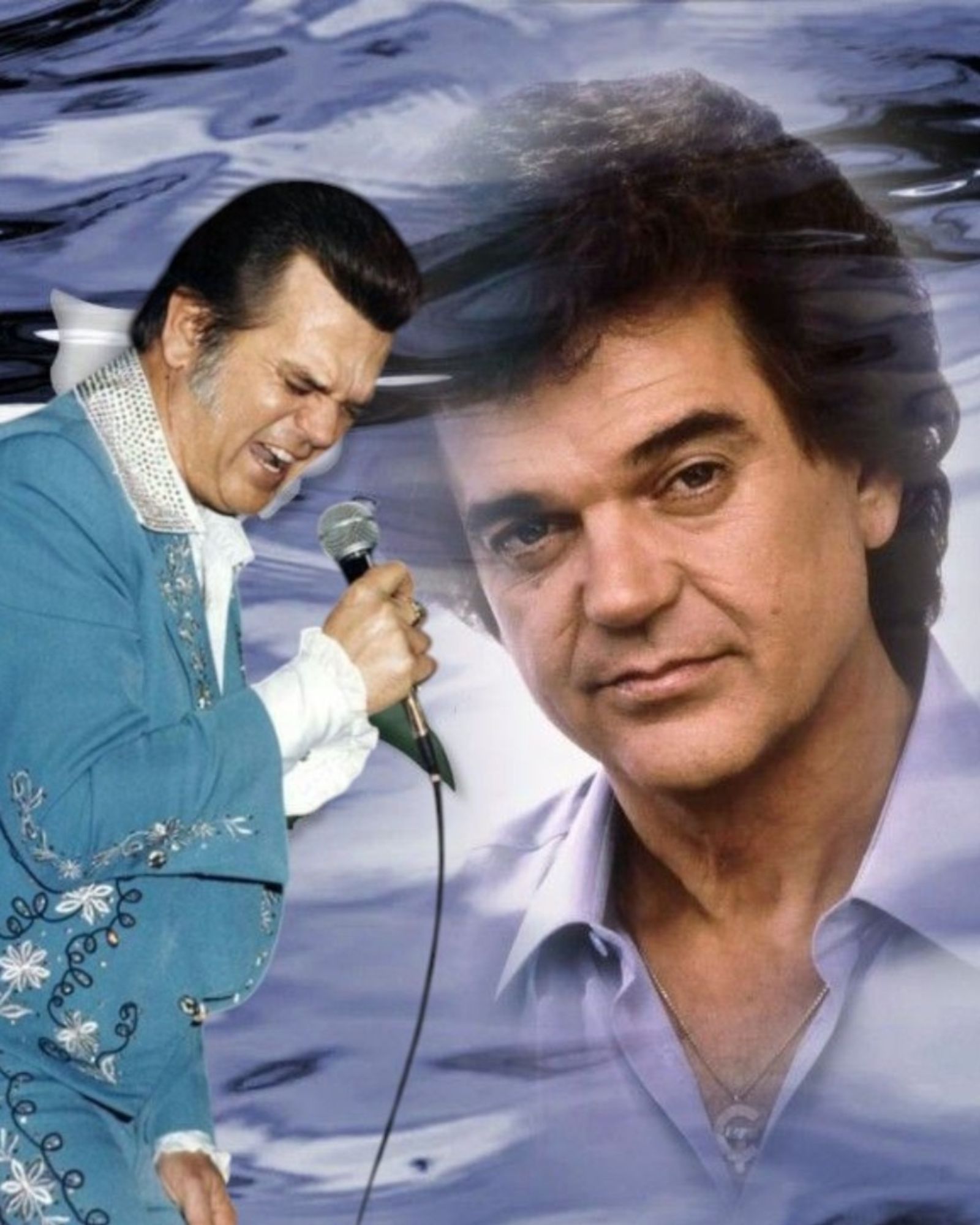

Was Conway Twitty singing to us, or was he confessing to himself? Millions heard his velvet voice and felt he was telling their stories, never realizing he might have been telling his own. Friends close to him later revealed that the king of love songs often channeled his own quiet heartbreak into his music, turning his performances into a form of therapy. It’s a chilling thought that for Conway, “the stage became his confessional,” and every fan singing along was an unknowing witness to a pain he couldn’t speak of otherwise.

I remember first hearing it not on the radio, but late at night through a thin apartment wall—the kind of muffled glow that turns melody into memory before you even register the words. A voice as warm as lamp light. A rhythm section that didn’t rush. The song felt like a hand on your shoulder, then a small nod toward home. When I finally learned the title—“I’d Love to Lay You Down”—it fit the sensation perfectly: a promise delivered in plain speech, steady and unembarrassed.

Released in January 1980 as the lead single from Conway Twitty’s album Heart & Soul, this track arrived at a moment when Twitty had already become a pillar of modern country music. It wasn’t a breakthrough; it was a refinement—another turn of the wheel from an artist who knew exactly how softly he could sing and still be heard. The single topped the country charts for a week and became his 24th No. 1, a milestone that underlined how secure his footing was by the dawn of the new decade.

Heart & Soul is a fitting umbrella for this performance, because the record’s best qualities are right there in the title: sincerity, patience, tenderness without syrup. Twitty produced the cut alongside David Barnes for MCA, another sign of his quiet authority in the studio. You can hear that authority in the way the arrangement avoids grandstanding; the shape of the performance is almost architectural, measured by lines and corners rather than fireworks.

The first thing that strikes you is the vocal placement—close, intimate, as if the microphone is inches away. Twitty’s phrasing stays conversational, with just enough vibrato to soften the cadence. You catch the little things: the attack of a consonant held back by breath; the tiny tail of reverb that clings to the end of a line like daylight holding to a windowsill. There’s no theatrical swell on the choruses. Instead, dynamics expand by degrees: a bass that fills in a touch more, a backing instrument stepping forward a half pace, a harmony line that knows when to smile and when to disappear.

It’s fashionable, especially in ballads, to make the big promise by climbing in key. Not here. “I’d Love to Lay You Down” does something unusual for a country hit: it modulates downward, loosening tension rather than ratcheting it up. That design choice undercuts any hint of braggadocio and replaces it with comfort—the momentum of settling in, not showing off. Musicians sometimes call this “demodulating,” and it turns the climax into a deep breath instead of a shout.

The arrangement is finely grained. Acoustic rhythm lays the floorboards, a quiet metronome of strums that never grow brittle. Electric accents appear like points of light—small chordal touches with a mellow edge, the kind you get when a player keeps the amp’s treble in check and lets the fingers do the shaping. The steel guitar doesn’t cry; it sighs. Fiddle, if present, behaves like a polite guest. A brushed snare suggests heartbeat more than backbeat. On top of that, a restrained keyboard sits in the midrange, suggesting the warmth of a living room upright rather than asserting a concert hall grand. All of these details tell you the same story: this is a piece of music built for proximity.

Twitty’s career arc by 1980 helps explain the song’s confidence. He’d traveled from rock ’n’ roll in the late 1950s to country royalty by the ’70s, and by Heart & Soul he was both star and craftsman. The songwriting credit goes to Johnny MacRae, whose lyric turns on a simple vow: a man insisting that the passage of time won’t dim his desire or respect. The pledge is earthy without being crude, and its most powerful tactic is restraint—less a seduction than a renewal of vows, delivered in a tone that implies the chores are done and the world can wait outside.

Listen closely to Twitty’s consonants—the “d” in “down,” the gentle “v” in “love.” He rounds them, keeps them inside the room. When he stretches a vowel, it isn’t to flaunt range; it’s to cradle the syllable. This is the kind of vocal that sells truthfulness rather than spectacle. You can almost see the singer lean away from the pop habits of the era, away from glossy crescendos, and toward the lived-in textures of everyday devotion.

There’s a pocket in the rhythm section that feels like mid-tempo swing walking in socks. The bass sits under the floorboards; the kick drum is a hush rather than a thud. If you’ve ever listened with studio headphones, you’ll notice how the mix leaves space around the voice, like a chair pulled back from the table so no one bumps into it. That negative space is part of the storytelling. It says: this conversation matters.

What about harmony? You get light refrains that don’t dare overshadow the lead, and they land with the courtesy of a front-porch response—someone across from you nodding yes, that’s right, yes. When the downward modulation arrives, those harmonies soften with it, trimming brightness, lowering the ceiling until you’re not standing in a hall at all but sitting in a room.

The lyric’s plainspokenness is another reason the song endures. Country music has always prized concrete images—dirt roads, kitchen tiles, worn boots. Twitty sidesteps the expected rural diorama and goes for something even more elemental: the promise of presence. You don’t need scenery to make it true. You need tone, patience, and a delivery that treats intimacy like good china, handled carefully every time it’s brought out.

Consider how the arrangement manages romance without perfume. The steel phrases are spare, the fills between vocal lines shaped like nods rather than flourishes. The acoustic part is steady, a hand that doesn’t fidget. And the electric guitar is supportive, the way a porch post supports a roof: you might not notice it until you lean.

Here’s the quiet paradox: for all its softness, the track is structurally bold. Lowering the key and declining the big, upward final chorus is a kind of artistic humility—and a challenge. It tells the listener: we’re not going to win you with altitude; we’re going to win you with temperature. “I’d Love to Lay You Down” is warm to the touch.

“Twitty doesn’t seduce so much as reassure, proving that devotion can be the most persuasive hook of all.”

The historical facts lock it into place. As mentioned, the single was released January 14, 1980; it served as the first single from Heart & Soul, written by Johnny MacRae, produced by Conway Twitty and David Barnes, and issued on MCA. It reached No. 1 for a week; some sources also note its standing as the 24th chart-topper of Twitty’s career, which testifies to the stability of his audience and the reliability of his taste.

A brief note on sound quality: the track benefits from the early-’80s country approach that liked clarity more than grit. Rather than saturating tape to get faux-rock heft, the engineers kept the voice and mid-range instruments distinct. It’s the kind of mix that translates well whether you’re listening through modest home audio or a car stereo that has outlived three registrations. It also means the song has aged better than many of its peers; there’s less dated gloss, more human breath.

Twitty’s interpretive choices underscore the lyric’s theme: the enduring beauty of a partner across years. He sings the idea of time like it’s a friend, not a rival. You hear it in the gentle pacing—no urgency, just certainty. That’s rare, especially in romantic songs that often hinge on chase or conquest. Here, romance has already arrived and decided to stay.

The emotional content gets richer the more you think about who might be listening. Picture a couple on their secondhand sofa in a rental they’re slowly turning into a home; the song gives them permission to find glamour in an ordinary Thursday. Picture an older pair, dishes drying, when the record lands like a note slipped into a lunch pail: still you. Or picture someone alone, the song acting as a rehearsal for the kind of love that isn’t hungry for novelty but grateful for presence.

From a musician’s perspective, there’s a lot to learn here about arrangement economy. You can trace what each instrument contributes and how nothing, not even a pretty lick, is allowed to tempt the song away from its central voice. The acoustic strum holds time, the bass outlines the harmony, the electric guitar sketches soft counter-melodies, and the keyboard fills the inner space with a pastoral warmth. If you’re new to recording, try focusing on the releases of notes—the way phrases end. The track is a seminar in how to stop playing without calling attention to the stop.

And if you’re a singer, the lesson is breath—and privacy. Twitty makes the listener feel like an invited confidant. He trades the preacher’s projection for the partner’s aside. That’s why the downward modulations feel earned: the story is descending to earth, arriving where people live.

Context within Twitty’s catalog matters as well. The late ’70s into the early ’80s saw him shading his sound in contemporary directions while keeping his core identity intact. You can hear experiments elsewhere—touches of soul and even rock influences across different singles—but “I’d Love to Lay You Down” strips away adornment and centers his most durable asset: a believable voice saying something worth believing. Historical notes from the Country Music Hall of Fame underline how this period marked a more contemporary polish paired with candid themes; this track exemplifies that balance.

There’s also a cultural angle that feels newly resonant. In a culture of constant upgrade—phones, feeds, even feelings—the song insists that love is a maintenance art. It’s not a sales pitch; it’s upkeep. Maybe that’s why it works across generations. Younger listeners hear a template for steadiness; older listeners hear recognition. You don’t outgrow a promise if you keep living up to it.

On a technical note for players: notice how the acoustic and electric parts avoid stepping on the vocal frequencies. In a mix, that’s protective design. The mid-range is shaped so that the voice wears the room rather than fights it. If you’re practicing at home and trying to emulate that hush, keep your strumming hand relaxed and lean into the downbeats just enough to suggest sway, not stomp. This is one of those recordings that can teach as much as any formal guitar lessons, precisely because the choices are audible and attainable.

I also return to the keyboard every time. It behaves like a memory keeper—sustaining a chord as if holding a thought. You can hear the harmony extend under certain lines like a rug being pulled a few inches farther into the room. It’s not about virtuosity; it’s about atmosphere—a reminder of what the piano can do when it thinks like a room rather than a spotlight.

Because the performance is so measured, small details shine. A slide in the steel that doesn’t tug too hard. A soft third above the melody from a background singer. The bass choosing roots and fifths with the calm of someone who knows flash is not the assignment. Even the fade feels deliberate, like a door closing gently so the rest of the house can sleep.

If you’re revisiting the song today, it rewards concentrated listening. Try it once with the volume low, as if you’re eavesdropping. Then bring it up just enough to feel the weight of the bass and the shimmer of the overtones. That shift in perspective mirrors the song’s own movement—from the general to the personal, from the promise that could be for anyone to the vow you intend for one person standing right there.

What keeps me coming back is the way “I’d Love to Lay You Down” locates romance in reassurance. Plenty of love songs try to dazzle; this one chooses to trust. And that trust, rendered in a subtle, downward-tilting architecture and delivered by a voice that understands the dignity of plain words, remains disarming.

Two final notes for context-seekers. For discography sticklers, the recording appears on Heart & Soul and has also been widely anthologized on themed collections. The official credits confirm Johnny MacRae as songwriter and Conway Twitty with David Barnes as producers on MCA. If you’re cross-checking chart history, multiple sources concur on the 1980 release and week at No. 1; what varies across summaries is the framing of its legacy, which, if anything, has only grown as the song has migrated to playlists and digital platforms over time.

If you want to hear more nuance in the arrangement—the small harmonic cushions, the air around the vocal—listen on a decent setup or even a good pair of studio headphones. The close-mic’d intimacy becomes even clearer, and you can track how each entrance and exit of a line subtly seasons the room.

In the end, this song doesn’t try to change your life. It tries to keep it—familiar, steady, deeply human. That’s its gift, and why it remains among Twitty’s most convincing declarations.

Listening again, I’m reminded that elegance can be as simple as care.